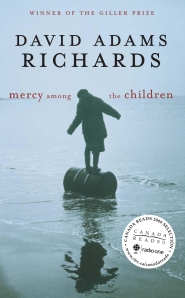

Mercy Among the Children

Mercy Among the Children

David Adams Richards

Doubleday Canada 2000

First published: Haliburton County Echo, County Life

2001

Review by: Kerry Riley

The year 2000 saw the welcome return of author David Adams Richards to the Canadian literary scene with the publication of his book, Mercy Among the Children, which most deservedly won the Giller prize (shared with Michael Ondaatje, and Anil’s Ghost) and has, as is often the case with Richards, been a source of controversy amongst the reading public ever since. In addition to the usual debate over how much gloominess is too much gloominess, which habitually dogs Richard’s work, there was the added issue of his move to Doubleday, and the acquisition of a new agent. There was, I think, a sense that the great marketing machine was about to SELL this book – and the guard was up. I’m happy to report that Mercy Among the Children rises brilliantly above all such considerations, including marketing backlash.

Lyle Henderson, a rough-looking 25-year-old former resident of the Stumps, in Miramichi, New Brunswick, appears suddenly at the apartment of Terrieux, a retired police officer, who years before, worked in Lyle’s home town. During his tenure there, Terrieux had saved a boy, Mat Pit, from drowning. An heroic act in itself, its consequences, as Lyle explains, were not universally positive. For Mat Pit went on to play out his role as the negative centre of a wheel of fortune whose radiating spokes touched many lives in the Stumps, none more negatively than Sydney Henderson’s, Lyle’s father. In the process of explaining the consequences of Mat Pit’s rescued life, Lyle tells the story of his father’s own heartbreaking struggle to live truthfully and non-violently, of a childhood pact with God, and its toll, and eventual implacable resolution. And, on a different order of magnitude, the justness of it all.

Sydney’s life, as the son of an occasionally violent, abusive drunk and ne’er-do-well is, until the age of 12, a pretty straightforward, if heartrending, hard-luck story. At that point, however, in a dispute over a molasses sandwich, he pushes another boy off a roof. Connie Devlin, the boy in question, falls 50 feet, and Sydney, staring at his motionless form, fears he is dead. In an act of rebellion against his birthright of violence and anger he vows to God that if Connie’s life is spared he will never again raise his hand or voice to hurt another person. The terms of this agreement will eventually cost Sydney his life. No sooner has he made it though, than Connie cracks a smile, rises up, and runs away laughing.

Despite the obvious prank, Sydney insists on honouring his vow. A brilliant, self-taught scholar, who at the age of fifteen had read Stendahl and Proust, he had come to see this path as the only way out of his family’s destructive past. Unfortunately, as an occupant of one of the lower rungs of Stumps society, physical and mental aggression are almost essential acts of self-preservation for him.

Sydney’s perceived passivity sentences him and his family to suffer endlessly from what Lyle identifies as, “the callous and chronic idiocy of others.” The children are ostracized and tormented. The family endures desperate poverty, physical bullying, condescension and false accusations of thievery, sabotage, pedophilia and even murder.

People, particularly Mat Pit, bend the truth of Sydney existence, because it’s undefended, into any configuration that best suits their situation. Lyle, in a frustrated attempt defend his family when it seems his father won’t, is seduced by the easy glamour of violence, falls in with Mat Pit, and seems well on his way to becoming just another small town thug heading for a bad end. Both Sydney and his wife Elly, die early, tragic deaths. Only Autumn, their daughter, manages to transcend her circumstances, and go on to lead the sort of life that reaps the rewards of Sydney’s sacrifice.

Readers who have followed Richards’ past work will find themselves in familiar territory in this book – the hardscrabble existence of residents of the Miramichi area of New Brunswick — and exploring familiar themes. Richards continues to delve into the pathos of unremarked, but noble lives. One recognizes shades of Ivan Basterache (Evening Snow Will Bring Such Peace, 1990) and Tom Donnerel (Bay of Love and Sorrows, 1998) in Sydney Henderson. He demonstrates again, the pounding that any simple truth will take in the sea of conflicting self-interests which inevitably surround it – those self-interests housed in a host of sharply defined, and unforgettable characters. Certainly there is the same fascination with moments of fateful decision, and the consequences of the choice made, and with that point in society where the privileged and the destitute meet, and the tension that exists there. The irony of good intentions, especially those of the “educated” classes, is once again exposed – opportunistic advocates of fashionable causes – the environment, women’s and native rights– all get a swipe. Even the CBC! Radio!!

It is regarding Sydney, and his behaviour, that reader opinion tends to diverge most. Those who dislike the book, express anger and frustration with his refusal to defend himself, and his family. The family’s trials, detractors complain, are too big and too many, Sydney’s behaviour incomprehensible, the story too relentlessly dark. I sometimes suspect that those who insist on this interpretation have not finished the book. Certainly, I think most readers follow, as I did, much the same journey as Lyle — experience his bewilderment, frustration, and sense of betrayal and anger. Along the way, uncomfortable questions inevitably arise. Sydney’s treatment by his town forces one to wonder just how welcome truth is, really, in our world, how compatible with our human natures? Readers might also rightfully ask, though, “Is it a sin to be too good?” If, like Sydney, we preserve our integrity at great cost to others? Yet Lyle, in the end, comes to believe, of his father, that “no man was essentially greater” and tells Terrieux, that in spite of everything “overall, it has been a life of joy.”

If you can entertain the idea that any individual life (perhaps your own) might only have purpose as a stepping stone for fate, then you may be on your way to making peace with Sydney Henderson. If not, he’ll remain an irritating and self-destructive enigma.

Whatever its debt to past efforts, Mercy Among the Children, is a step forward for Richards. The old concerns are there, but concentrated and distilled, honed to a sharpness that may, admittedly, make even the steadiest reader flinch. Sydney is clearly an allegorical figure – integrity incarnate let loose amongst the mortals – his struggles mythic. His short, and unbearably hard existence was the sacrifice that altered his family’s destiny, providing a bridge to a better life for those of his children who could cross it. Like those giant hieroglyphics which only make sense when seen from far overhead, the joy in this story is best appreciated from a vantage point far above the everyday concerns of individual lives. That place where all great stories come from.

_______________________

For those Canadian shoppers interested in ordering from an independent Canadian bookstore, your best bet is to use the “Find an Indie Bookstore Near You” option, and click on an individual store’s web page link.

Pingback: Richards, David Adams: Incidents in the Life of Markus Paul | Kerry On Can Lit

Pingback: Integrating Can Lit by Subject Area in the Senior Grades: some suggestions | Kerry On Can Lit