Richards, David Adams

Richards, David Adams

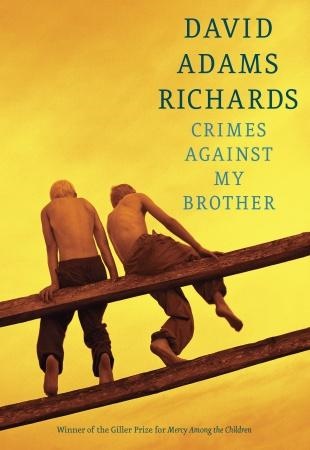

Crimes Against My Brother

Doubleday Canada, 2014

Hardcover, 400 pages

In his latest novel, Crimes Against My Brother, Richards returns, as is his wont, to the Miramichi River, in his native New Brunswick, to once again cast a gimlet eye on the doings of men. Something of a companion piece to his 2000 Giller Prize-winning Mercy Among the Children, this tale focuses on a new generation in the small mill town, although the history and mythology of the area, created by Richards over forty-some years, inform the story throughout. Sydney Henderson, the protagonist of Mercy Among the Children, makes a number of appearances, as does Markus Paul, from Incidents in the Life of Markus Paul. The Jameson Mill, immortalized in The Friends of Meager Fortune,

stands in ruin, a signpost to the past, and Good Friday Mountain looms over it all.

The plot is intricate (flow charts are helpful) and told by an unnamed narrator who left the area when he was young and is now a tenured university professor. He tells the story of three of his younger cousins, Evan Young, Harold Dew, and Ian Preston, who grew up together in the Bonny Joyce/Clare’s Longing stretch of the Miramichi in the 1970’s. Echoing the accepted wisdom of the town, the boys share a contempt for the local scapegoat, the older Sydney Henderson (of Mercy Among the Children) who, in that earlier story, made a pact with God, eschewing violence forevermore, and who insisted on honouring this vow even though the circumstances under which he was compelled to make it were almost immediately revealed to be fraudulent. Sydney’s rejection of violence, even in defense of his family, is interpreted as selfish and weak, the pact viewed as a smokescreen for timidity. Although, in reality, largely the result of human malevolence, his family’s destitution and persecution are seen as proof of the general uselessness of his God and the simple-minded futility of his faith.

It came to pass (the scope and tone of the story invite biblical diction) that in March of 1974, the three boys, mostly as a result of the negligence of Lonnie Sullivan, a local “wheeler-dealer,” and conniver of the highest order, find themselves trapped for three days on the side of Good Friday Mountain in an ice storm, their survival far from certain. Made reckless and majestic with the knowledge that their lives hang in precarious balance, the boys mock Sydney Henderson’s pact with “a Catholic God they did not know or believe in,” and determine to make their own pact — to “cut for blood,” and become blood brothers. In a scene worthy of any great confrontation with the elemental forces of the universe, against a backdrop of “pulsing darkness,” thunder, pelting snow, and the mesmerizing glitter of a vein of fool’s gold illuminated in the flash of lightning, the boys mix their blood and hurl their challenge into the void, goading God to demonstrate his power, and exhorting each other “to be heroic and loyal.”

So they agreed, although they might face death right here, this terrible night, or they might come out of it — whatever happened, life or death, pitiless or free, they would rely upon one another and no one else.

Obviously, in the interest of the story, they survive. The rest of the novel is preoccupied with a minute examination of the various and sundry ways in which the three friends subsequently betray each other, and those around them, aided and abetted by the townspeople, a sort of malicious, dysfunctional Greek chorus, with Lonnie Sullivan as their titular head, always ready to reinforce the darker aspects of the boys’ natures, rationalize a selfish act, encourage ungenerous sentiment, or disseminate gossip. Distinguishing themselves from this general nastiness are several individual characters of remarkable goodness — Sara Robb, crippled as a girl as a result of her heroism in saving her younger sister Ethel (also a force of good) and Molly and Corky Thorn, Evan’s wife and brother-in-law, respectively.

Almost immediately, the world as it is begins to make a mockery of the boys’ proclaimed loyalty and devotion. Lonnie Sullivan, a trickster-like agent of chaos and conflict, functions as a sort of traffic coordinator for the various challenges to which the blood brothers’ pact will be subjected. The first arrives in the form of a tragedy as Harold’s mentally impaired younger brother Glen is killed while filling in for Harold (who was late to work) on a job for Lonnie Sullivan. Harold (no doubt battling guilt of his own) is easily manipulated by Lonnie into believing it was Evan Young who had insisted on going ahead with the job using Glen, when, of course, it was really Lonnie who pushed to have this happen. As a result, Harold and Evan are estranged. Already on shaky ground, the pact is, in short order, challenged again by those two great human preoccupations, love and money. While at times, as in the case of Glen, Lonnie’s influence is simply a logical consequence of his mendacious nature, in these subsequent situations his machinations are deliberate and vindictive. Enter Annette Brideau, an ethereally beautiful but shallow young woman and unwitting minion of her “uncle” Lonnie, who comes between Ian Preston and Harold Dew as they compete for her favour, and for whom Ian will betray his fiance, and Annette’s best friend, Sara Robb. The Good Friday Mountain pact is delivered a final death blow as a result of a misunderstanding over an inheritance. Joyce Fitzroy, related to all three boys, is a slightly addled village elder and drunk, but has amassed a relative fortune of over $100,000. Speculation over who shall end up with the money is a favourite sport in the town. Harold is considered the best bet, although Evan hopes to at least negotiate a loan in order to fulfill a dream of resurrecting the old Jameson mill. Both expectations are dashed however, when Ian, who had no real designs on the money, almost accidentally ends up with it under circumstances which lead Evan to believe (erroneously) that Ian deliberately double-crossed him.

The story follows the main characters, Ian, Harold, Evan, Annette, Lonnie, Sara, Ethel, and Corky through their lives, as their fortunes wax and wane, and they struggle with the choices life presents them. Their lives unfold against a backdrop of financial uncertainty and labour strife, government cunning and ineptitude, and corporate iniquity as a Finnish-Dutch multinational successfully conspires to exploit the last great stand of timber in the area, bilk the government of millions in incentive money, and, in the end, destroy the local mill by shipping the lumber to Quebec to be processed. It is, above all, a tale of betrayals, both personal, spiritual and civil.

Crimes Against My Brother is Richards’ most overtly spiritual work to date — with a clear sense of fate, and of universal justice. Prophecies, premonitions, portents, inexplicable but provident urges, and supernatural references abound, and the wind curls, lashes and riffles through it all like the breath of the deity.

Uncharacteristically, for me, when dealing with Richards’ work, I have some reservations about this novel. All the spectacular strengths of his writing are present — the grand reach, the magisterial rhythms, the minute and often compassionate understanding of human motivation and struggle to be good, the unerring ear for dialogue, unforgettable characters, and the keen comprehension of our multi-layered societal structures. There are, in short, many reasons to recommend this book. Yet, the parts do not assemble themselves into a satisfying whole in quite the same way as Mercy Among the Children or Incidents In the Life of Markus Paul. Why? Like so many holistic things, the magic inherent in a masterpiece is not necessarily susceptible to logical analysis, but several issues can be identified which contribute to the malaise of this work. First, as mentioned earlier, the plot is notably complex, and ideas tend to repeat themselves. The incisive narrative organization generally so characteristic of Richards’s work at times collapses in a welter of detail. Secondly, while Richards is well-known for his criticism of the academic intelligentsia, and outright contempt for a particular type of narrow, self-satisfied academic, the tone here veers, at times, perilously close to peevish. The framing device of the story — that it is being recounted by a professor of social science who had personal ties to the town, and who had subsequently used the story in his course lectures — feels extraneous. It does not seem to serve any essential purpose beyond providing a soap box for rather one-sided anti-academic sniping. At times, the sniping feels uncomfortably personal. In a work already suffering from a surfeit of narrative lines, this one might best have been dropped.

To admit to issues with the book is not to say that it is not still thought-provoking, and at times monumental. As noted earlier, it is helpful to consider this story as a companion to Mercy Among the Children, in which Sydney Henderson disavows violence in a pact with God and subsequently suffers mightily at the hands of men, before an early, tragic death. Crimes Against My Brother functions as the other side of the dialectic: life with God (Sydney) versus life without God (the boy’s pact), or the religious life versus secular humanism. Think of it as a sort of Lord of the Flies, with God standing in for the “grownups.” Richards states this idea directly, through his narrator:

Let Syd do as he would; they [the boys] would do as they did, and they would see who triumphed in the end.

The fact that the boys’ determination to be existentially self-sufficient without any need of religion is in tatters in very short order is a clear indication of Richards’s own sympathies. More prosaic readers might, however, point out that, in practical terms, Sydney’s fate was far worse. This is true. Yet, counter intuitively, in Mercy Among the Children, his son, Lyle Henderson, describes his father’s life as a life of joy. Furthermore, despite the tragic end which we know awaits him, and his present vicissitudes, Sydney, in this story, is remarkably certain, at peace with life, free of ego, avarice or resentment, and, yes, joyful. In several instances he offers clairvoyant guidance or insight to key characters, but to little avail. Indeed, he seems to have attained the status of a holy man, sage or prophet, able to see, with remarkable clarity, the intricate inter-connectivity of life, and thus, understand the future. There is a sense, as well, that beneath the surface contempt, he is beginning to earn a grudging respect amongst the people, and that, over time, his stature will grow. Although it is true that, for some of the boys, life works itself out tolerably, joyful is not a term that can be reasonably applied to any of their fates. Both Sydney and the boys suffer at the hands of men, but taking the longer perspective (as Richards inevitably does) it seems a life with a spiritual component is preferable to one without.

There’s been a lot of God-talk, thus far, and I’m acutely aware that, on the surface, without some insight into Richards’ concept of the divine, the plot summary above could be confused with a Watchtower mailbox missive, and is undoubtedly making readers nervous. A curious agnostic myself, I have no patience with narrow, religious orthodoxies, and any suspicions that Richards was, in Crimes Against My Brother, adopting an exclusive, Christian, Catholic viewpoint would provoke an upsetting rift with a writer I have very much admired. Just these sorts of concerns led me to his earlier non-fiction work, God Is (2009) in an attempt to pin down his position on the troublesome God issue. Written, I suspect, in reaction to some of the more extreme anti-religion polemics from the likes of Dawkins and Hitchens, it is, to be sure, a sometimes rambling and confusing work, but one which did clarify many of the ideas explored in Crimes Against My Brother. Although Richards is quite cagey about defining his exact concept of god, often demurring about his own understanding, but then slipping, almost by default, into a comfortable orthodox Christian, Catholic expression, I was convinced by the end, that the divine is, for him, a broad, complex and evolving idea. As Richards himself explains, “[he did] not agree with the faithful (or at least all they said), so much as disagree with the unfaithful (…).” He comes closest to articulating his worldview, perhaps, in Crimes Against My Brother as Corky Thorn (one of Richard’s innocents: see below) attempts to explain to Ian, that life exists within a shimmering web of interconnected actions, and that fate manifests through these interconnections:

He tried to impress on Ian that Ian’s sudden and impulsive decision about Sara had caused much unhappiness, and that he was coming to understand how the world was created by such numerous untold events, formed in the vast air about us on a daily basis. “Maybe even on another dimension!” he shouted, to make himself understood.

Perhaps most pertinent to Crimes Against My Brother are Richards’ observations that the divine is not to be found externally, but is

the human foundation of knowing in our own heart what is good and valuable in the spirit. What is wrongdoing and what is not.

and that

To not take this [sin, wrongdoing] seriously is in fact to not take anything in our lives seriously.

These ideas were explored somewhat more obliquely in Incidents In the Life of Markus Paul, in which a community’s relationship to truth was minutely examined, and sin identified as an inappropriate stance in regards to it. In Crimes Against My Brother, they are tackled head on. Each character’s fate is connected to the degree to which they recognize their own inner knowledge of good and evil, and the seriousness with which they attend to this knowledge. Sydney, who has come to understand his own innate divinity, sees clearly how he must act, and is free to lead a spiritually joyful life, aware that while this may not be easy, it is right. Harold, Evan and Ian, however, in the act of rejecting God, have, in fact, denied the best part of themselves and of others, and are doomed to betray and be betrayed. (Betrayal, or, more broadly, sin, in Richards’ terms, being the defeat, within ourselves, of what we know to be right, in favour of what we think we want.) The seduction scene between Annette and Ian, in some of Richards’s most powerful and exact writing, at once implacable and compassionate, illustrates this idea of betrayal beautifully, as each character’s understanding of right is defeated in a series of small acts of self-deceit. Within this small, and very personal scene, Richards seems to be saying, lies the inevitable defeat of humanism. We all try to be good, he says but we all “find, sooner or later, a wall in [our] soul [we] cannot climb.”

Familiarity with God Is provides a number of other helpful insights into Crimes Against My Brother, which, in the interests of brevity, I’ll present in list form:

1. Physical objects often act as sort of spiritual vectors (in an epidemiological sense). That is, they serve to illuminate the interconnectedness of our lives, the fatedness of circumstances, in spiritual shorthand, the presence of the divine. The wrench, the fur hat, the buck knife, the antique trunk, and Harold’s shotgun all serve to highlight for the reader particular paths of connection in a universe of infinite connection.

2. Richards quotes G. K.. Chesterton, who said that “Coincidences are spiritual puns,” which goes some ways in explaining the rather startling number that occur in the story. In fact, for Richards, there really are no coincidences — they are simply a manifestation of an infinitely complex, divine order in our lives.

3. Richards believes that while most of us embody good and evil in varying proportions, there do exist people who are naturally good. They have a clarity which is often mistaken for simple-mindedness, but in fact comes from an intuitive understanding of the divine. They tend to be childlike, and exhibit a spontaneous goodness which shows in their faces, making them attractive whether or not their conform to standard ideas of beauty. Sydney, is of course, the prototype, but in a lesser way, also Corky Thorn, Ethel and Sara Robb, and Ian and Annette’s son Liam.

The reach of this novel is epic — nothing less, really, than a dissection of the human condition. It will make you think. And, if the reach just exceeds the grasp — well, I do imagine Richards, with a grin and a shrug, reminding us all that, after all, that’s what a heaven’s for.

________________________________

Newsflash! September 10, 2014: Crimes Against My Brother being adapted for television.